Subject: Philosophy

Topic: P4C – Philosophy for Children

Age Group: KS1 & KS2

Synopsis:

Why teach children philosophy? Since philosophy is all about asking questions, children are instinctive ‘’philosophers’’. Philosophy can teach your pupils to think more clearly and to be confident in debates and discussions. Socrates, one of the greatest philosophers, pretended that he knew nothing and then he showed people that their ideas were wrong. Transform your classroom into an ancient Greek agora to re-enact a debate on a philosophical enquiry to show your children that all answers and ideas are correct.

This pack exemplify how philosophical enquiries and the use of picture books can be incorporated into sessions for all ages and across curriculum, bringing something important to the life and learning of children. During the intensive discussion, children will have the opportunity to develop critical thinking and reasoning skills as they make sense of arguments and counterarguments.

The National Curriculum already includes the directive to promote critical and creative thinking across curriculum. Teaching philosophical skills provides children with the tools for enquiry and helps them to unlock their curiosity. Philosophical enquiry enhances learning in English, Citizenship, RE and PSHE. Among the key skills in the National Curriculum, one of the most prominent is communication. An ideal way to improve the quality of both thinking and communication skills in school is to introduce the discipline of philosophy into the curriculum. P4C promotes critical and creative thinking and emphasises the importance of questioning, collaborative enquiry and dialogue, whose roots lie in the Socratic method. Through philosophical dialogue, students develop understanding of abstract concepts such as fairness, normal, good or bad, love. They learn the language of debate and gain an understanding of the difference between argument and quarrelling. In fact, the benefits of teaching philosophy are endless, but the best skills and attitude for children to learn are those that will help them to think for themselves.

Wanda Gajewski

Wandsworth LRS

Librarian’s view:

“Cogito, ergo sum: I think, therefore I am.”

Rene Descartes

Philosophy began thousands of years ago. The earliest philosophers on record lived in ancient Greece is around 600 BCE. Philosophy means ‘love of wisdom’. We all use this method to understand ourselves, and our world, by asking a lot of questions. However, when we are introduced to the idea of philosophy with children, we may be dismissive. The first point to make therefore, is that this is practical philosophy – the process of exploring philosophical questions through Socratic questioning.

Children ask questions and want to understand everything better and see it more clearly. Not all children’s questions are philosophical. So, what are philosophical questions and how can you use them in the primary classroom? Philosophical questions are thought-provoking. They open enquiry, rather than closing it down with a single answer. Pupils will learn that each answer to their previous question raises the next question.

Too begin the philosophical enquiry, pupils make statements such as, ‘I don’t know how old God is’. You can explain to the children that all their statements can be turned into questions. In this way, children learn to ask questions on their own. Your pupils develop the fundamental skill for philosophising which will inspire independent, critical thinking. Philosophical enquiry ignites the curiosity of the world and other people, empowering children in the learning process.

The programme of philosophical enquiry for children was developed in the 1970s in the USA by Philosophy Professor Matthew Lipman. The aim of the approach was to develop mental and communicative competence in children, including justifying their own judgment; explaining concepts; interpreting and listening to others.

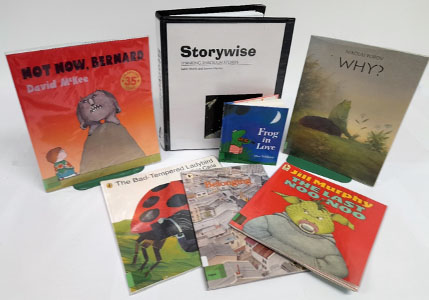

Central to P4C (philosophy for children) is the use of the stimulus. All kinds of stimuli can be used but perhaps the richest opportunities lie in the use of stories. In the early 1990s Dr Karin Murris, a Dutch philosopher working in Britain, wrote about the potential of picture books for eliciting interesting philosophical questions from children. Now, picture books provide a rich stimulus for P4C. The format of the picture book is one already very familiar to young children, and they have both the text and illustrations on which to base their questions. There are a wealth of good quality picture books which are suitable for philosophical enquiry that will enrich your lessons.

Resources

Tusk Tusk

by David McKee

Once upon a time all elephants were black and white; they hated each other. The whites lived on one side of the jungle, the blacks on the other. One day they decided to kill each other. Peace-loving elephants from both sides escaped to the darkest jungle and were never seen again. One day the grandchildren of the peace-loving animals appeared, and they were grey! Since then the elephants have lived in peace.

This story is simple, but the book’s colour and layout powerfully emphasise ‘difference’ and provokes a strong and emotional response from readers.

First, let your children immerse into listening to the story and then go on to exploring the picture book by asking questions. What is this story is about? Is it right to hurt other people or animals? You will keep your class hooked on the story as the young children usually welcome opportunities to discuss moral issues in a structured manner.

Where the Wild Things Are

by Maurice Sendak

Max is wearing his wolf suit and making mischief, his mother calls him ‘’wild thing’’ and he retorts, ‘’I will eat you up’. She sends him to bed without his supper. In his room a forest starts to grow, and the walls become ‘’the world all around’’. Max steps into a boat and sails off to a place where Wild Things are. He tames them and they make him the king. After a while, Max feels lonely and wants to be where someone loves him best of all. He sails home and finds his supper waiting for him in his room.

Read the story with your children and look at the illustrations. Tell the children that you are interested in their ideas and responses. Then, by asking a question, for instance ‘’What is a dream?’’, you begin the discussion with your pupils. This story will raise ideas around anger, love and dreaming as some of the intriguing angles for a philosophical enquiry.

Dinosaurs and All That Rubbish by Michael Foreman

A factory owner orders his workers to build him a rocket. The trees are cut down, coal dug and anything that needs to be burnt is burnt. The launch of the rocket is from the top of a waste heap. The factory owner lands on the moon, but there is nothing to see or admire. There are no trees, flowers, or grass. He is disappointed and chooses to travel to Earth. In the meantime, on Earth, the heat caused by piles of rubbish disturbs the sleeping dinosaurs. They are shocked by the mess and the smell and decide to have a good clear out. Flowers, grass and trees start to grow again. When the man lands on Earth he doesn’t recognise the planet and exclaims that the has found his paradise. This time the Earth belongs to everyone. The dinosaurs emphasize that no parts belong to any one person, but that everything needs to be looked after by everyone.

This picture book focuses on obvious environmental issues and animal rights and conveys a message that we are all responsible for looking after our planet Earth. Let the children work in pairs and invite them to write a few questions, for example ‘’What is a paradise?’’. Then the pupils explore and discuss some of the philosophical concepts.

Zoo

by Anthony Browne

Zoo tells the story of a family of four visiting a zoo. The eldest of two sons, who is the narrator, tells us about the traffic jam on the way up. He thought that the traffic jam and the animals are all boring, but are the animals bored too? The family appears to be more interested in themselves rather than the animals. The highlight of the day for our narrator was the lunch of burger and chips, his brother liked the monkey hats best, while his dad liked going home best. That night the boy dreams of being in a cage and the story ends with his question: ‘’Do you think animals have dreams?’’.

The thought-provoking images, combined with the influential text, evoke strong emotions, and also give a platform to many ethical questions: animal rights and freedom, for instance.

Let your pupils formulate questions and ideas. Ask the children what is their answer to the boy’s question at the end of the story, ‘’Do you think animals have dreams?’’. Children’s questions and observations will form a base for future sessions and debates.

Michael

by Tony Bradman

Michael is a boy who does not fit in at school. He persistently refuses to conform, while pursuing his own interests in flying and spacecraft. He is often in trouble and his teachers give up on him. At the end of the story he flies off in a rocket he has constructed, after independent research, from recycled parts. The teachers then claim that they knew he would go ‘far’.

Michael is an amusing and powerful story. This book touches on all the major themes in philosophy; for example, freedom, the needs of the individual, good and bad. Let the pupils think about their own school experiences and ask them to generate some questions related to the school, curriculum and favourite subject. Your pupils will welcome the opportunities for discussing school rules, classroom behaviour and what it means to be free.

Facilitate a discussion

When teaching P4C (philosophy for children) you might also like to use Storywise: thinking through stories by Karin Murris and Joanna Hayes

Another useful resource when teaching P4C (philosophy for children) is But Why? Developing philosophical thinking in the classroom by Sara Stanley