Alan Gibbons

Tens of thousands of school children have met Alan Gibbons. But his influence goes much deeper than as an author of more than 70 books, including a Blue Peter award for The Book You Couldn’t Put Down, Shadow of Minotaur (2000), and a huge fan of School Library Services (SLS). Find out more about the author who launched National Libraries Week. Interview by Nicola Baird

Q: How can you tell if a school is good?

The good ones are where the library is the first thing you see out of the foyer. If a school has a library, it tends to be good; if the library is run by some sort of qualified librarian it tends to be good. If books are not just presented spine-on, that’s good. If corridors have posters about reading that’s good – there are a whole series of clues.”

Alan Gibbons, author and library champion

“I was restless as a young person,” says Alan Gibbons from his home in Liverpool. “I was a working class kid who went to university in the 1970s and then couldn’t settle into anything. I did teaching, journalism and many factory jobs.”

He finally settled into teaching in his 30s, doing all he could to put information in front of his students. “As a teacher the School Library Service (SLS) was essential for us. I was English co-ordinator and I didn’t have the budget, particularly in non-fiction, for the breadth of reading. SLS wasn’t just delivering a huge number of books and tapes, there were wonderful artefacts – Papua New Guinean masks, pottery from Somalia – that schools could use.”

“At a primary school in Knowsley I once created a Somali fishing village with all these artefacts including macrame umbrellas. The class was 99 per cent white working class Scouse kids and getting a picture of a totally different world with books like Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman and Handa’s surprise by Eileen Browne. Some of the kids I taught barely went into Liverpool, never mind knew the world beyond,” he says.

In 1990 Alan wrote his first book, Pig, about a runaway pig causing havoc inspired by something he saw coming home from school when he was growing up in Crewe. His tip for pinning down a good story is to be aware that: “Writing is about curiosity, so any trigger works: write what you know and what you don’t know and are curious about. I also like writing and reading about people on the run.” Taking his own advice one of his favourite titles is The Edge (2002) about domestic violence and racism featuring a flight, with a lad and his mum running from an abusive boyfriend. His 70+ books include titles for Barrington Stoke, several Carnegie nominations and many, many happy readers.

“In some shape or form except when taking the dog for a walk I’m reading all the time: fiction and non-fiction and poetry endlessly. For information and for pleasure.”

Alan Gibbons, author and library champion

Celebrating libraries

The first nationwide celebration of the UK’s libraries was 4 February 2012 – a happy occasion marked by author talks and competitions. But this new National Libraries Day was born out of a wide-reaching campaign to stop politicians slashing library budgets, which had been given a boost when Alan Gibbons got involved.

“The campaign started taking shape when I was asked to fill in for Michael Rosen (Children’s Laureate from 2007-2009 and author of We’re Going On a Bear Hunt) in Doncaster. I turned up at a pub and was told £800,000 was being removed from the library budget. My jaw hit the ground and I started to email all these authors I had on my email list. Philip Pullman (author of His Dark Materials) was the first to reply. I knew austerity was bad, but it never occurred to me that a town the size of Doncaster could have a spending cut of nearly a million quid,” says Alan.

“As we entered 2010 this was happening everywhere. Public libraries were under pressure, but I also started to hear horrible stories when I was doing school visits. For example, the library in Jersey was OK, but there was a story of the school down the road with a head teacher and a load of suits going into their library and saying ‘right, we’re ripping all this out and it’s going to be a computer room’, in front of the librarian. She burst into tears because she knew she was going to lose her job.”

The next few years were non-stop campaigning.

“I’d love to say we were successful, but we’ve lost hundreds of libraries and a lot of school librarians have been made redundant. We had two big lobbies of Parliament, numerous petitions, readings and demonstrations starting from the British Library,” says Alan.

Another passionate advocate of keeping libraries open was the Children’s Poet Laureate Julia Donaldson, author of the wonderful Gruffalo. “When we met Ed Vaizey and he said he was ‘a Gruffalo fan’, she tore into him saying, ‘If you and your children love reading why are you denying it to people less fortunate than you?’”

“We campaigned more than any other public service, but the sheer scale of the cuts did sweep us away. Every librarian knows we’ve suffered far more than we should have done from years of austerity. Even if you don’t win doesn’t mean that you’re not right! When I go to Finland, Switzerland, Holland – anywhere – nowhere do I see the carnage of public libraries that I see here in the UK. And in Korea and Japan library spending went up,” adds Alan who has had some satisfaction seeing National Library Day morph into a regular celebratory week for the UK’s much-loved libraries in early October (3-9 October 2022).

“The scale of spending cuts forced on this country damaged the structure of libraires and generated an atmosphere in schools that school libraries are seen as less important. But almost every head teacher is talking about rebuilding a culture of reading. We did a petition of 7,000 people calling for school libraires to be made statutory with a properly trained school librarian. We’ve got libraries in prisons, why not prevent people going to prison in the first place by giving them libraries at school?” asks Alan fiercely.

In Liverpool

After visiting more than 2,000 schools all over the world, from nursery to sixth form, on author visits and seeing his four children grow up Alan calls himself “basically retired”. In fact, Alan, 68, continues to be frenetically networked since becoming a councillor for Warbreck in the May 2020 elections. “Liverpool is one of the most deprived constituencies in the UK, though my ward is one of two better off ones, with many working class families in work. Nearby in Everton the average household wage is £13,000 for a family, that’s about surviving not living,” he says fresh from the annual budget battle.

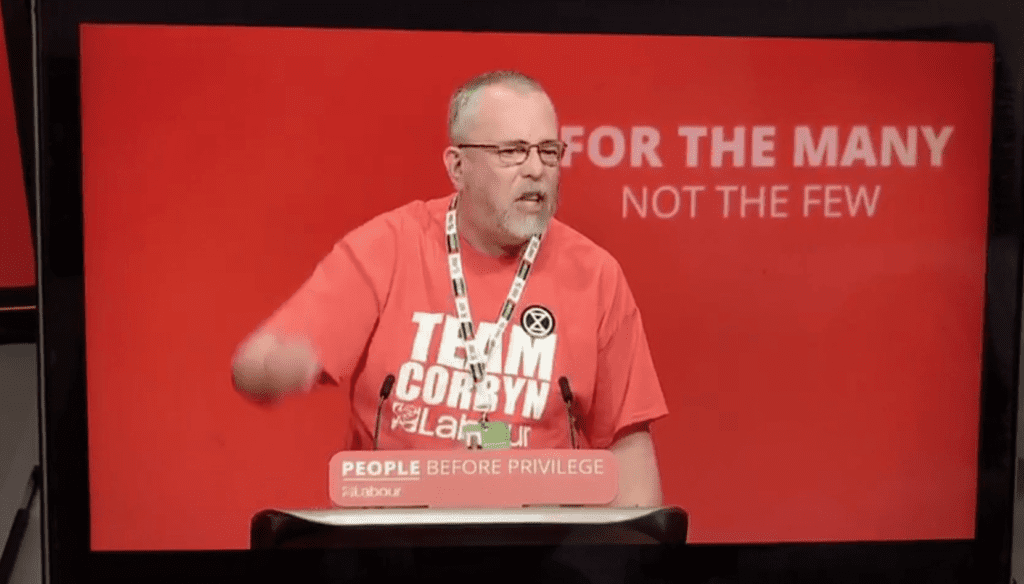

Politics is as much a part of Alan’s identity as books and football, all football. Wikipedia charts his commitment to Marxism via the Socialist Workers Party and then the Labour Party headed by Jeremy Corbyn. “I’ve been a socialist since I was 14, seeing what was happening with civil rights in America and Ireland (1968). I was at a course in 1971 at the Sorbonne in Paris and went on quite a few scary demonstrations – attacked by the CRS (French security police) – and read a lot of Régis Debray (French philosopher, friend of Che Guevara and inventor of mediology) and a number of anarchists’ work,” he says providing a definitely romantic start to his political activism.

In contrast his feeling about libraries has been a lifelong constant. “I can’t remember a book shop in town other than Smiths, so as a kid Crewe library gave me access to literature. I’d go in on Saturday morning and borrow three books – I loved the Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Biggles and lapped them up when there were rainy days. When it was sunny, we were always out. As I got more academic, I’d find French, German and Latin in the library. People talk about their passion for libraries, but for me it was just there, like the police station, the butchers – a natural organic part of life. I never thought it couldn’t be there,” he says.

Five or six decades on Alan is one of many authors, librarians, booklovers – actually anyone who needs a book – who is still a passionate library fan, though these days he reads “everything online”. Right now, that’s a thriller set in Libya by Merseyside-born Steve Howell, called Collateral Damage. Somehow the title seems to hint at the painful story of the way children’s love for reading has been treated by austerity focused politicians closing library services.

- Alan Gibbons tweets @mygibbo

- Stay up to date with @librariesweek and look for #SpeakUpForLibraries

- Libraries Week 2022 is 3-9 October